Jakarta, PWYP Indonesia – The weakening of the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) was carried out systematically through revisions to the KPK law (UU No. 19 of 2019) to the latest through the implementation of the National Insight Test (TWK), which led to the elimination of KPK employees with integrity and successfully handled cases of grand corruption involving political party officials, members of the DPR, and senior police officers. Publish What You Pay Indonesia (PWYP), in collaboration with the Cross-University Anti-Corruption Movement (GAK LPT), held a webinar to provide an understanding to the public about the KPK’s significant role in eradicating corruption in the mining and natural resources (SDA) sector. Present as a resource person in this webinar, Sujanarko (former Director of Inter-Commission Network Development and Agencies (PJKAKI) KPK); Hania Rahma, an academician from the University of Indonesia and anti-corruption counselor; Faisal Basri, a senior economist from the University of Indonesia; and Maryati Abdullah, senior advisor to PWYP Indonesia. Then Arip Yogiawan from the Indonesian Legal Aid Foundation (YLBHI) acted as moderator in this webinar.

Sujanarko, former director of the KPK PJKAKI, started the discussion by comparing the conditions of eradicating corruption before and after the reformation. Many international funds come in loans, grants, or investments to domestic, but the inflows of these funds damage democracy in the pre-reform period. “The international funds cannot be monitored so that international supervisors cannot monitor the use of these funds,” said Sujanarko.

This condition reversed after the UNCAC (United Nations Convention Against Corruption) was held after the reform, namely in 2003. With the establishment of the KPK in the same year, international supervisors were greatly helped by the existence of the KPK, which was able to monitor the use of international funds at the domestic level. Nevertheless, post-reform political conditions are still marked by the absence of vertical accountability of public officials and political parties that do not represent the interests of the Indonesian people, and Indonesian natural resources are controlled by foreign investors who act as beneficial owners.

Then the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) began handling natural resource corruption cases in 2007. Bribery cases involving regional heads and company leaders are often dismissed without causing a deterrent effect due to short prison sentences and the consequences of shell companies. The KPK also conducts studies and provides recommendations to improve the governance of the natural resources sector, such as the One Map Policy and the initiation of the National Movement to Save Natural Resources (GNPSDA).

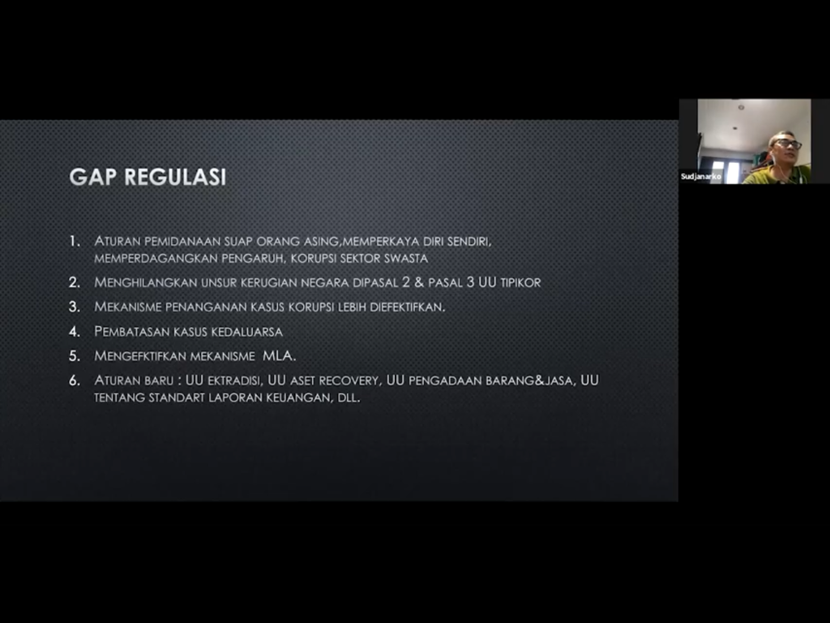

Private sector bribery). Sujanarko believes that high political costs, high rents from the natural resources sector, and oligarchs who enter political party activities foster corruption in the natural resources sector. He offered to reform political parties through the implementation of SIPP (Political Party Integrity System). In addition, he also encouraged Indonesia to close the existing regulatory gaps such as punishment for bribery of foreign public officials, illicit enrichment, trading in influence, and private sector corruption.

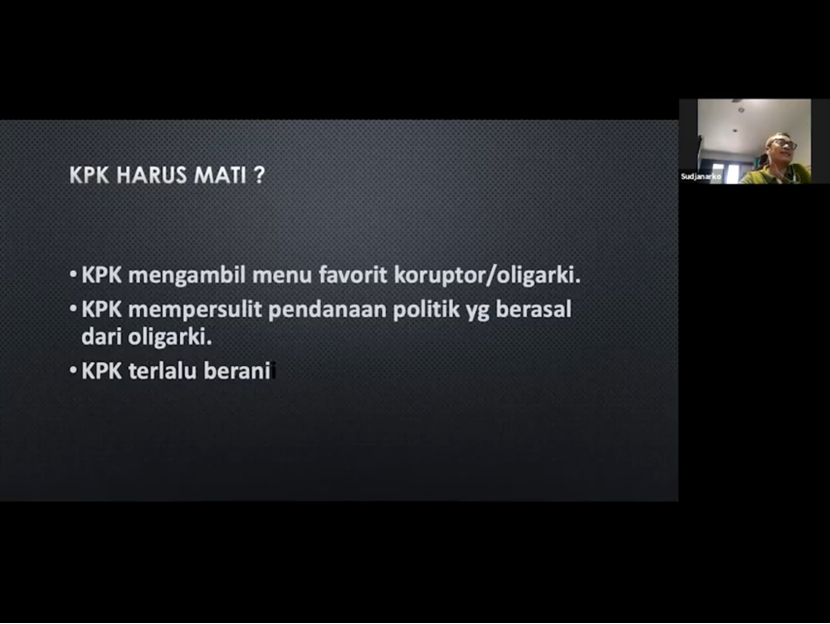

The weakening of the KPK through the National Knowledge Test (TWK), Sujanarko argued this time the KPK was weakened because of an internal “attack.” He predicts that the KPK will be paralyzed in the future. “Supposedly, we do not depend on the bureaucracy, but depend on a structured society,” said Sujanarko.

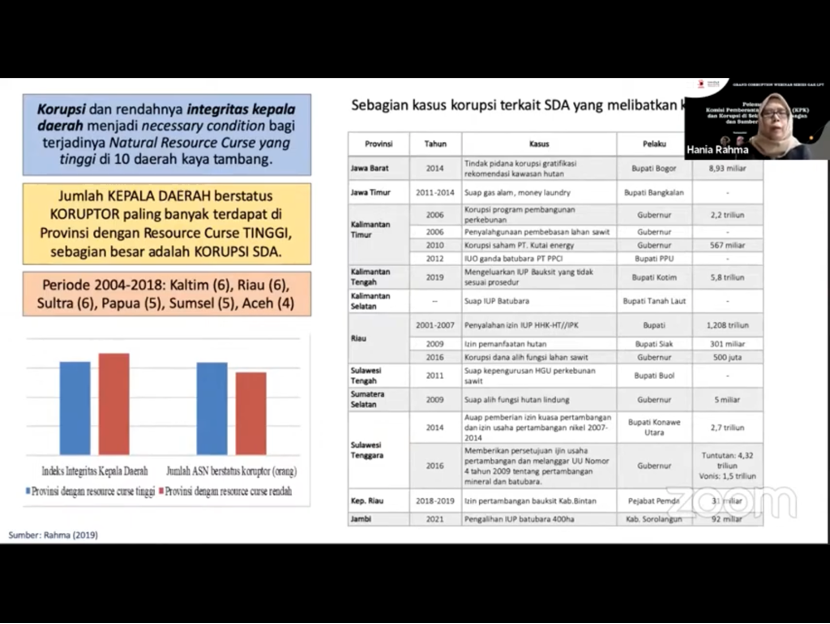

Meanwhile, Hania Rahma, an academician from the University of Indonesia (UI), explained that regions dependent on natural resources tend to experience the natural resource curse phenomenon. For example, East Kalimantan, Riau, and West Papua have not succeeded in prospering the people in these areas, even though these areas have very considerable natural resources (SDA). “High corruption and low integrity of regional heads are factors that cause the natural resource curse,” said Hania Rahma.

She argued that the natural resources sector is the most accessible sector for funding for political parties because of the enormous rents from this sector. In addition, corruption in the mining sector is also common because mining corruption can be carried out for decades and only stops when natural resources are exhausted. Therefore, handling corruption cases in the mining sector, which is considered quite tricky, is also one of the biggest obstacles in eradicating corruption in the mining sector.

As a solution, Hania Rahma is pushing for urgent policies through natural wealth valuation maps and the Natural Capital Index (NCI) in order to determine the value of natural assets so that compensation for environmental damage due to natural resource extraction can be determined correctly, the establishment of incentive and disincentive schemes in the management of natural resources through fiscal transfer policies. , as well as the establishment of a Natural Resource Fund for the sustainability of natural resources for future generations.

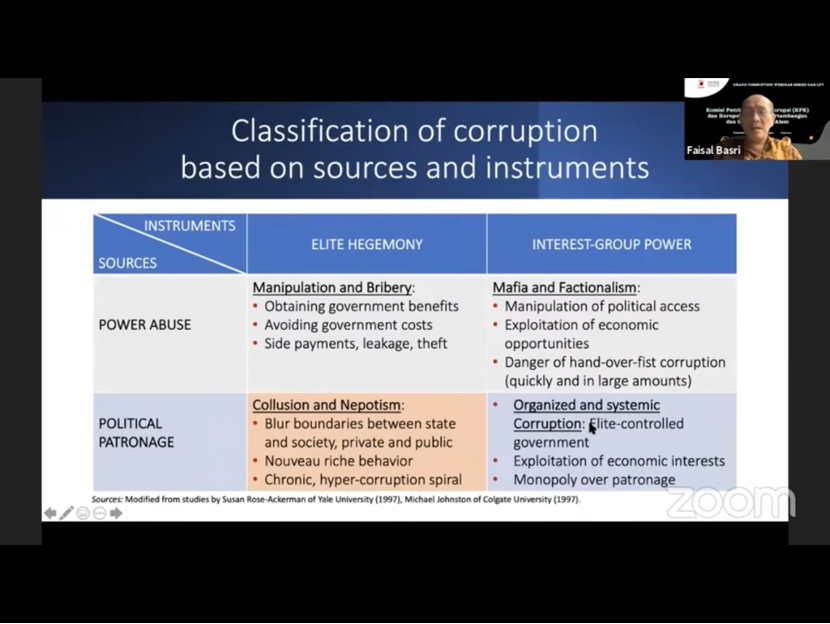

Meanwhile, Faisal Basri started his presentation through the concept of grand corruption, specifically the abuse of power at the top level that benefits a few people, harms the people, and gets impunity. He thinks that grand corruption in the natural resources (SDA) sector can occur because corruption is legalized.

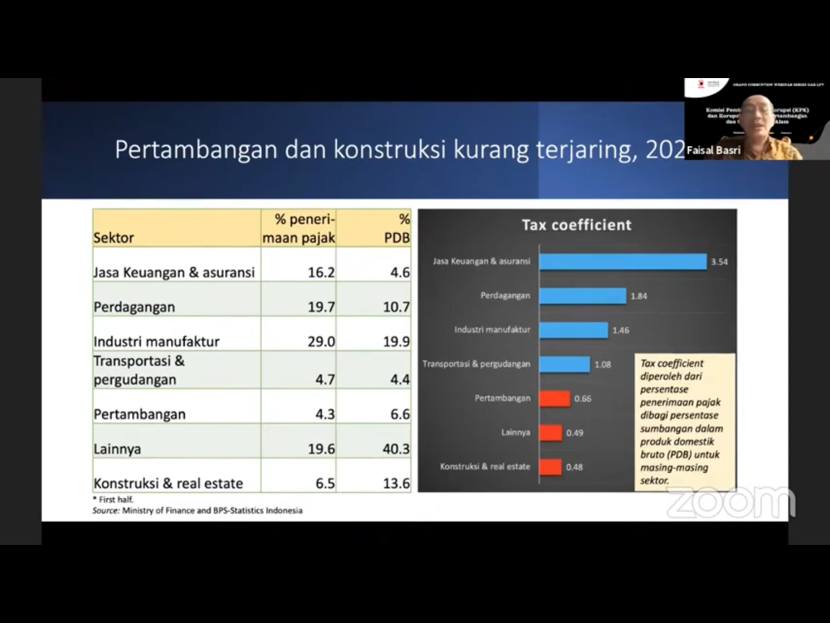

Faisal Basri highlighted the decline in taxes in the mining sector—as seen from the mining sector’s tax coefficient, which was only 0.66. “The low coefficient is caused by corruption and facilities that exempt taxes for entrepreneurs in the mining sector,” said Faisal Basri. In addition, he also explained that investment in Indonesia is not of high quality. Indonesia’s ICOR (Incremental Capital Output Ratio) ratio has the most significant leakage in Southeast Asia.

As a solution, Faisal Basri demanded that an audit of the provision of tax facilities (tax holiday) be carried out and an audit of the investment value which is likely to be marked up.

Meanwhile, Maryati Abdullah highlighted corruption that occurs along the mining sector’s value chain, from licensing and revenue collection to transfer mispricing facilitated by shell companies. The political structure dominated by the oligarchy and the existence of the legal mafia further exacerbates corruption in the natural resources (SDA) sector.

She argued that apart from tax oversight, law enforcement supervision, press independence, and strengthening public control, and academic freedom is an essential element to strengthen democracy and support evidence-based policies. “If the campus does not have independence, the campus will have the potential to become a supporter of actors who weaken the anti-corruption movement,” said Maryati Abdullah. (FY)