30 June 2015, Andi Fachrizal, Sanggau, West Kalimantan

Antonius Anam could not breathe easily. That afternoon, he looked confused. In fact, the clothes he wore were random with a collared shirt that revealed his chest combined with shorts. Yet he ignored all of that.

In front of journalists who visited his residence in Subah Village, Tayan Hilir District, Sanggau District, the Head of Subah Hamlet presented his ideas. “There is no other choice for us except to secure the remaining customary areas,” said Anam, Tuesday (9/6/2015).

The statement on the issues was also witnessed by environmental activists from Lembaga Gemawan, Swandiri Institute, and the New Perspective Foundation inseparable from the chaotic status of Subah Village. The village with a population of 2,207 people is included in the conversion production forest (HPK) area. Instead of obtaining a land certificate, because of this status, extractive industry permits have penetrated under the residents’ houses.

“This issue continues to haunt our minds. If you look at the status of the area, the land where the villagers’ houses are now is clearly state-owned land, we’re just freeloading. But the fact is, we have been living here since the time of our ancestors,” he said.

Anam’s worries came to a head when industrial permits entered. Environmental conditions are increasingly hostile. River water is polluted with sewage, and fish are hard to find. Apart from the mining industry, the surrounding area of Subah Village is also surrounded by oil palm plantations.

Anam and a number of local community leaders have repeatedly made efforts to prevent the company from cultivating customary areas, sacred places, and sources of livelihoods such as springs. However, this step is often stumbled by the lack of knowledge of the villagers.

The residents of Subah were only able to save part of Bukit Satok. That too is limited to Pedagi. Pedagi is a sacred place that is used for rituals of local beliefs during the harvest season.

Inside the Pedagi there are graves of the predecessors. In addition, there is also a stone of worship. Because of its importance, the residents of Subah Village were defended by the threat of the company concession.

Until one day, Lembaga Gemawan and Swandiri Institute researchers were present in the midst of the people of Subah Village in 2013. “Friends at that time did not come empty-handed. They offer a technology to help carry out participatory mapping, “said Anam.

Long before that, the indigenous people in Subah Village only relied on customary recognition to control an area. However, to map customary areas is not possible only with index capital.

Citizens need maps. This step was taken as the basic capital to be submitted to the government in order to release the area from the burden of company permits. But until now, the process has not yielded the results as expected by the villagers.

The carrying capacity of the environment is getting weaker every time. The rivers and lakes are no longer a paradise for fishermen. “I can’t rely solely on my livelihood as a fisherman. Now we have to find a side income such as cutting rubber, ”said Sukarjo (40), a resident of Subah Hamlet.

Sukarjo has been a river fisherman since 1990. At that time, his income as a fisherman was enough, even more, to support his family. “We can earn an average total income of IDR 10 million per month. But now, getting IDR 2 million per month is difficult, ”he said.

Customary forest plans

Subah Village Secretary, Toni, confirmed Sukarjo’s statement. According to him, the majority of residents of Subah Village are now in a vortex of economic problems. “Hence, we are trying to push an area of 12 thousand hectares to become customary forest. These areas include hills as a source of water, pedagi, and tembawang,” he said.

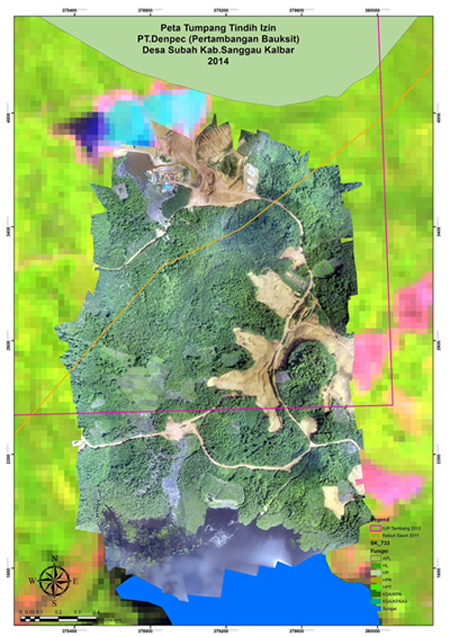

Toni admits that the company pays less attention to environmental aspects. This is also the basis for the villagers to do something for their survival. “We finally received assistance from a participatory mapping program from friends Gemawan and Swandiri using drones,” he said.

Even though they are small and simple, the presence of drones among the Dayak Tobag indigenous people in Subah Village is very useful. This unmanned aircraft technology is able to provide significant assistance. The form is in the form of a customary forest plan map.

Researcher at the Swandiri Institute, Arif Munandar, said that the area of mapping of customary forests in Subah Village which was carried out by drone had reached 3,000 hectares. “We think these areas are very important to be protected through custom,” he said.

The head of Subah Village, Kanisius Kimleng, appreciated the steps of its residents. “Although I am not active in taking care of customary forest initiatives using drones, everything is smooth. I’ve been represented by Pak Sekdes and Pak Kadus. So, we share our duties so that all village government affairs run, “he said.

Source: http://www.mongabay.co.id/2015/06/30/hutan-adat-subah-yang-menanti-sentuhan-negara/