By Karl Decena

Commodity Insights

Indonesia plans to shorten nickel mining quotas to one year from three years to help limit oversupply, but the plan is unlikely to boost prices and may create

bureaucratic headaches for miners, according to industry experts.

The resource-rich nation said in early July that it would reinstate one-year mining production quotas, known in Indonesia as RKABs, starting in 2026.

Indonesia expects the move to boost prices and raise government revenues, but it may not be enough to revitalize the nickel market, industry experts told Platts,

part of S&P Global Commodity Insights.

“Unless enforcement becomes more stringent, the move is likely to introduce more administrative uncertainty for miners, instead of actually curbing oversupply in

the near term,” Jorge Uzcategui, a senior analyst covering cobalt and nickel at London-based Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, said in an email.

Subdued price impact

All mining companies in Indonesia must secure an RKAB to determine the quantity of ore they are allowed to extract. The government extended the validity to three years from one year in 2023 to reduce the frequency of reapplications. Three-year RKABs provided more regulatory certainty for miners, but the approval process was slower and they contributed to a supply surplus as the market did not fully absorb the output.

Reverting to one-year RKABs would help Indonesia better manage mineral oversupply while supporting prices, Bahlil Lahadalia, Indonesia’s minister of energy and mineral resources, said in early July during a parliamentary hearing. More money for the government would help President Prabowo Subianto achieve economic goals such as annual GDP growth of 8% by the end of 2029, the last year of his term. In April, Indonesia raised royalties on various minerals including ore containing nickel, copper and gold.

“We need to ensure domestic and export needs are balanced with production plans. There must be no more games. This is about protecting our national interest,” Bahlil was quoted as saying in a July 2 report by the Indonesia Business Post.

“This oversupply has led to price collapses and eroded the value of our strategic natural resources,” Bahlil added.

The RKAB change may not move the needle in the big picture, according to analysts. The nickel market has been experiencing a downturn due in part to excess Indonesian supply after the government banned the export of nickel ore in 2020.

Many nickel processing facilities subsequently set up shop and Indonesia is now the world’s top nickel producer. The country produced 2.3 million metric tons in 2024, representing 59.7% of total global output, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence data.

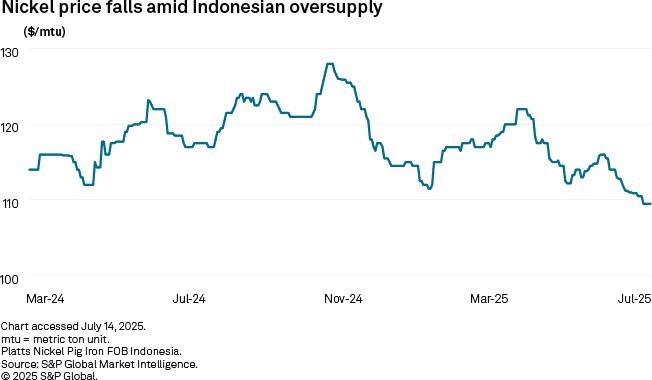

Prices have dipped due to the oversupply. Platts assessed nickel pig iron with 10% nickel content at $109.50 per metric ton unit (mtu) FOB Indonesia on July 14, down 14.5% from $128.00/mtu on Oct. 23, 2024, the highest since the assessment began in February 2024. The Indonesian government also decreased the annual nickel ore mining quota in early 2025, to 200 MMt from 240 MMt.

The global nickel market has also suffered with the US’ tariffs further dampening the demand outlook. The London Metal Exchange nickel price was $14,995.76 per metric ton as of July 11, plummeting 52.1% from $31,281.00/t on Dec. 7, 2022, the peak since a short squeeze drove prices to unprecedented levels in March 2022.

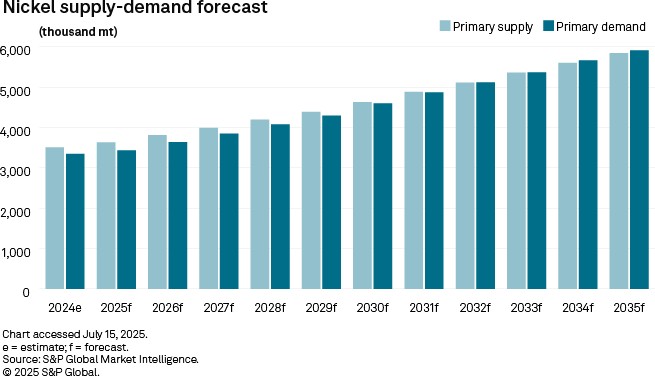

The near-term outlook remains bleak. The nickel market is expected to record a surplus of 198,000 metric tons in 2025, the fourth straight year that the market would be oversupplied, according to the latest Nickel Commodity Briefing Service report by Commodity Insights’ Metals and Mining Research team. The surplus is forecast to eventually dip to 12,000 metric tons in 2031 before swinging to a deficit of 5,000 metric tons in 2032, according to the report.

“The price impact is likely limited in the short term — sentiment remains driven by market fundamentals, including oversupply, slowdown in demand growth, and sizable inventory levels,” Uzcategui said.

More red tape

Some miners are not pleased with the planned RKAB reforms. Indonesia’s nickel miners’ association, APNI, called for the government to retain three-year RKABs.

“The government needs to strengthen internal evaluation and oversight capacity, not lengthen the bureaucratic chain with shorter licensing periods,” APNI said in a statement in a July 4 Reuters report.

Shifting to annual RKAB approvals may discourage miners from investing in long-term projects, said Thomas Radityo, an equity research analyst at PT Ciptadana Capital, an Indonesian securities brokerage company.

“The increased regulatory uncertainty may discourage long-term investment, potentially constraining future supply in strategic sectors,” Radityo said in an email.

Balancing act

Radityo suggested the implementation of a tiered RKAB system to balance the interests of the government and miners. Under a tiered system, new or high-risk producers would receive one-year permits for stricter monitoring and more established miners would obtain longer permits.

This model would balance regulatory oversight with efficiency while incentivizing good corporate behavior, Radityo said.

But for Publish What You Pay (PWYP) Indonesia, a civil society group, annual permits are more ideal as they would strengthen environmental oversight of the mining industry, which is marred by pollution and other sustainability issues.

“PWYP Indonesia supports the shift to a one-year RKAB. However, PWYP Indonesia emphasizes that the policy’s success hinges on robust implementation and risk mitigation,” Aryanto Nugroho, national coordinator at PWYP Indonesia, said in an email.

This article was published by S&P Global Market Intelligence and not by S&P Global Ratings, which is a separately managed division of S&P Global.